Huntoon grew up in Topeka, where she was a pioneer in the field of art therapy, working for Dr. Karl Menninger at the Menninger Clinic.

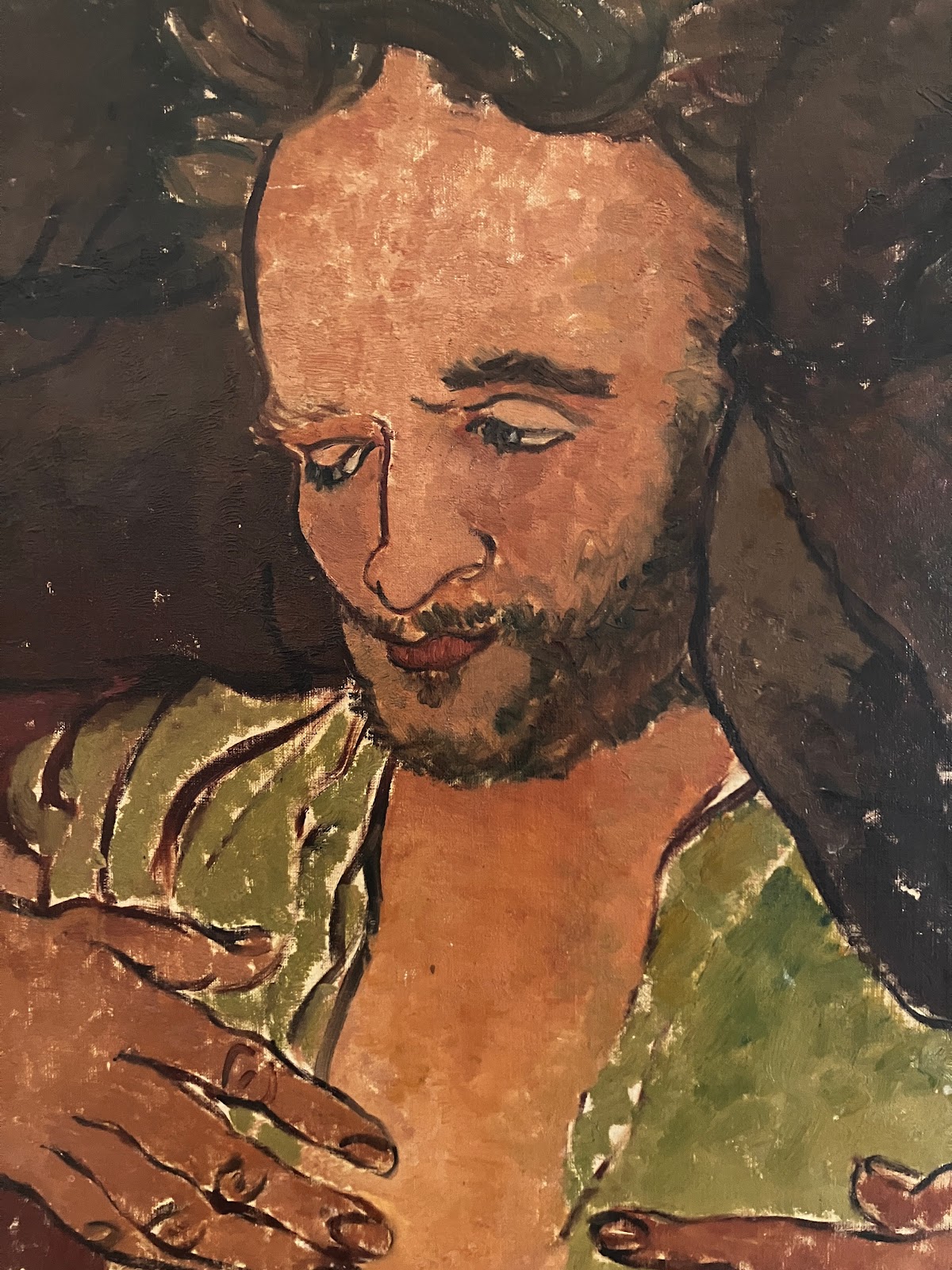

Huntoon trained at The Art Students League of New York and worked in Paris for five years. Huntoon’s own artistic style might be called expressive realism. Her graceful lines are similar to the style of Suzanne Valadon (1865-1938), a Parisian artist who worked in Montmartre at the turn of the 20th Century.

Huntoon’s great-grandfather Joel Huntoon was a Topeka pioneer who mapped out the Topeka street plan, including Huntoon Avenue.

Mary Huntoon was born in 1896 and raised on a cattle ranch until age 8 when her mother moved to Topeka and remarried. They lived in the old stone Huntoon home at 219 Huntoon Ave.

Huntoon was editor of The World newspaper at Topeka High School, and contributed art to the student yearbook. With a desire to become an artist, she attended Washburn University. George M. Stone, a highly paid portrait painter, taught her landscape and portrait painting.

After graduating from Washburn in 1920 Huntoon married Charles Hoyt, a veteran who served in France in World War I. He was a journalist and writer. The two moved to New York City where he worked as a writer and editor for the New York Evening Sun and the New York World-Telegram.

Mary Huntoon attended the New York Art Students League for six years, alongside Ben Shahn and Mark Rothko. Her anatomy instructor George Bridgeman taught students to develop discipline and stamina to withstand criticism. Her metal plate media instructor was Joseph Pennell, a leading American etcher and illustrator. Huntoon quickly learned the skills etching and printing and was a good draftsman.

Mary Huntoon attended a lecture class by Robert Henri, a beloved and charming teacher, who championed women students, as well as the American experience as art. He encouraged artists to paint as they wished, and to portray their subject as they themselves felt about it, not simply a representation of its outward appearance. She emulated his style to a certain extent. His painting, the Beach Hat in 1940, is similar in style to portraits that Huntoon painted in her later years.

In 1926, Huntoon went to Paris. She had only intended to stay for a few weeks, but ended up staying five years.

In Paris, she fell into a crowd of Montparnassians who gathered at Le Dôme Café at 108 Boulevard du Montparnasse. Le Dôme, which is still operating today, was an intellectual gathering place for artists and writers, particularly the American literary colony, during the interwar period. Letters archived at the Spencer Research Library at the University of Kansas show Huntoon had a wide ranging group of friends at Le Dôme. Her friend Edith “Nellie” Thain writes that their mutual friend “Abbie continues to drink too much, and judging from what I saw the other day does not eat enough.”

Other friends include Mr. Hogg, Oscar Gray, Moreton Hoyt, Ludwig and Wally. “Mr. Hogg is back.…I always suspected him of having a weather eye out for you. Ludwig thinks this is disgusting,” wrote Edith “Nellie” Thain in Nov. 4, 1930, letter to Huntoon.

In 1929, Huntoon wrote that Paris has greater sympathy for artists than does any part of the United States. "Paris appreciates and encourages the artist. His struggle for material is less, and is often given a chance to work out his own destiny without some of the handicaps facing him in the United States," she wrote. Her sixth floor apartment and studio in the Latin Quarter became a focal point for much activity, according to research by Mary Lou Casado, author of Mary Huntoon: In Search of the Meaning and Duty of Modern Art, a book Casado submitted to KU for her bachelor of arts with honors in April 1980, now located in the Topeka Room at the Topeka and Shawnee County Public Library.

In 1926, Huntoon demonstrated her etching technique to Stanley William Hayter, who gave his first print, Bottles to her. Both studied burin print making under Joseph Hecht in Paris. In 1927, Hayter created the Atlier 17 studio in Paris for etching and engraving. Pablo Picasso, Joan Miró and Wassily Kandinsky visited his studio to make prints.

Huntoon stayed in Paris alone, leaving Charles Hoyt, her husband back in New York to carry on his own work, Casado wrote. But in 1927 he joined her for a nine-month stay on the island of Corsica. Mary Huntoon had her first show at the Galerie Sacre du Printemps, Paris, in 1928. Seymour De Ricci said her paintings had robust brush work, and original, colorful, broad flat tints. Her etchings were refreshingly original.

Charles Hoyt carried out a hoax to test attitudes using the synonym George O’Keefe, writing a letter in the Paris edition of the New York Times, referring to Mary Huntoon, insisting no woman has distinguished herself in 5000 years and it is a little late to begin hope. Readers immediately responded with disgust for the misogynist, defending Mary Huntoon, and other women artists, said Sherry Best, art collection curator at the Alice C. Sabatini Gallery at the Topeka and Shawnee County Public Library.

Unfortunately, during the height of her success in Paris, her beloved husband, Charles Hoyt died in late 1928. His health was never very good since being gassed in World War I, and he died struggling with tuberculosis. Nevertheless, she stayed in Paris for another year after his death.

Casado’s book says it’s unclear why Huntoon left Paris, but she was perhaps like other ex-patriots who discovered that while they loved Europe, they were deeply American. I can relate. When I lived in Greece and Spain in 1990, I gained a lifelong fascination for Europe, but I felt a longing for the Great Plains, where I eventually returned to work as a journalist, marry and raise children.

Yet her time in Europe sustained her for the rest of her life. Huntoon wrote, “The net result of living in old Paris and Europe is that I feel more than ever the newer civilization of the states and more specifically the pioneer states and my dream has changed.”

In the 1930s, she taught art at Washburn University, including etching, painting and art history. In 1932 she married Lester Hull, who worked in the art department at Washburn. After they married, they studied and painted in Germany, Czechoslovakia and Italy. When they returned, she continued to immerse herself in the art world. Lester Hull had health problems and required constant care and attention. This was too much of a burden for her and eventually they divorced and he returned to Chicago to be near his sister. He died in 1948.

In 1934 she worked for the Public Works of Art project, later the Federal Art Project, created by the Civil Works Administration under President Franklin Roosevelt. She did several works of art under the FAP until 1939.

In the late 1930s she was also working as an art therapist at the Menninger Clinic. Dr. Will, Dr. Karl and their father Dr. C.F. Menninger founded the Menninger Clinic in 1925. Using Freudian concepts, they believed that trauma or conflict hiding in the subconscious is discernible and curable through psychoanalysis and psychotherapy. Therapeutic activities might include woodworking, garden therapy, music therapy and art therapy.

“It was never just busywork,” said Dr. Bob Conroy, a retired Menninger psychiatrist. “Dr. Will wanted activities to help patients deal with their pathology.”

Everyone at the Menninger Clinic was involved in therapy, whether it was the nurses, the doctors, the janitors or the cafeteria workers who all offered kindness and friendliness to the troubled patients.

Principal mediums in Huntoon’s art department were oil painting, clay modeling and engraving. Huntoon said Ruth Faison Shaw used finger painting at Menninger’s Southard School for children.

Rosemary Menninger, daughter of Dr. Karl Menninger, met Ruth Shaw in the 1950s when Rosemary was probably around kindergarten age. Ruth was a friend of Rosemary’s mother.

“My Dad told me something when I was working in garden therapy,” Rosemary recalled. “He said, ‘don’t fall into the trap of analyzing the person by trying to interpret what they are planting. Instead, focus on the fact that they’re working on something and bringing it to fruition. Is it the idea that they are creating and cultivating something that is more important.”

Writing in the Bulletin of the Menninger Clinic in November 1949, Mary Huntoon quoted Freud as saying the creative process is a way to keep destructive tendencies at bay. Picasso claims that a painting is worthy of the name of art when it takes charge of the painter at a certain stage, in other words, when the creative process is aroused in a person, it is a liberating agent for unconscious material of the mind.

While working at the Winter VA Hospital in the 1940s, under the direction of Dr. Karl Menninger, she found that art therapy could fall into four categories, including fantasy or wish fulfillment. Sometimes the patient expresses fantasies which are a prophecy of what is to come. For example, when a bedridden patient came to the studio in a wheelchair, he painted himself outdoors in a daisy field.

The second function of art therapy is dexterity, this helps the individual gain strength and security at developing a skill. The third function of art therapy is relief of anxiety. By drawing or painting, the patient puts down in a graphic way the aggressive and traumatic feelings that are deep in his subconscious. This is a form of art synthesis.

The fourth function is externalization and mastery of subjective thoughts and emotions. A patient who was diagnosed with psychoneurosis, anxiety type, with an obsession for masturbation, was too self-conscious to paint the first day, but the second day began with encouragement to try to put some paint on canvas just to get a feel for it, Huntoon wrote. Over time, he began trying to paint still lifes, including a trash can. This marked a turning point; painting became fun. He painted several credible paintings during a two-week leave. Through his paintings, this patient turned his emotional expressions into socially acceptable forms, thus gaining some mastery over his emotions, so that he was no longer at their mercy, Huntoon wrote.

“Another very important function is the interaction with the art therapist,” Conroy said. “My good friend, art therapist Bob Ault (who worked at Menninger) encouraged the patient to draw or paint, but that was only the beginning. He also was part of the therapeutic team and participated in the patient evaluation. He was able to use the conversation and comments the patient made to help with the treatment. Thus, there was a double benefit. The first was the art work itself which tapped the unconscious and hidden dynamics. The second was a psychotherapy process as the patient interacted with the art therapist. The process of creating the art often took away the fear that some patients had of interacting with a traditional therapist. Bob Ault and the therapy team worked together with many patients and the therapy was greatly enhanced by this joint effort.”

Huntoon worked in art therapy for about three years at the Menninger Clinic and 12 years at the VA, serving thousands of patients, most with no formal art training. She exhibited her students’ works, believing recognition of their talents was therapeutic, Casado wrote.

Huntoon was a pioneer in art therapy because of her contributions to the emerging field in the 1930s-1950s. In the 1970s and 1980s, authors like Arthur Robbins more clearly defined art therapy as a profession. His book The Artist as Therapist is a popular book in this field. In a discussion on colors, Carl Jung says green is for sensation, yellow for intuition, red for feeling and blue for thinking.

Mary Huntoon is largely unknown, but her work is popular in Kansas and the Midwest, and can be found in the Spencer Museum at the University of Kansas, the Topeka and Shawnee County Public Library, and the Mulvane Museum and the Newark Museum of Art.

Sherry Best, art curator for the Alice Sabatini Gallery at the Topeka and Shawnee County Public Library, said Friends of the Topeka and Shawnee County Public Library has been selling duplicate Huntoon prints through Soulis Auctions, Lone Jack, Mo.

When Mary Huntoon died in 1970, her third husband donated her remaining artworks in her studio to the Topeka and Shawnee County Public Library, said Best. Two of her paintings now hang in the library’s reading room; other paintings and prints are stored in the basement.

Best recently gave a tour of the library’s Huntoon collection to me and artist Luke Van Sickle. Her work is contemplative, somber, harmonic, philosophical and sublime. She is one of the best portrait painters in Topeka's history. She was an excellent educator and effective art therapist. Best said her clients usually got better after working with her. Huntoon stayed in Topeka, partly because of the opportunity to work with Dr. Karl Menninger. Had she stayed in New York or Paris, she probably would be more famous today, Best said.

No comments:

Post a Comment