By Michael Hooper

Eccentricity is misunderstood. Eccentrics are different, but not necessarily mentally ill. They tend to be independent, self-reliant, non-conforming, entrepreneurial people who are content in their creative pursuits; they might seem a little self-absorbed in their ways, but they are genuinely “happy” people. Eccentrics provide a unique perspective on life, which might not otherwise exist in their community. Their independent thought might be seen as strange, revolutionary, odd, but there’s often wisdom in their convictions. They suffer rejection, but carry on anyway.

This article features three eccentric men: Charles “Bogey” Savage, who lived in a sod house in Northwest, Kansas, near the town of Almena; S.P. Dinsmoor, the folk artist from Lucas, Kansas, creator of the Garden of Eden, and Ed Klattenhoff, who made and wore his own skirts in Hooper, Nebraska, in the 1980s, long before transgender issues were a big deal.

Bogey Savage

Charles Homer "Bogey" Savage was born in a sod house on March 6, 1879, to Charles and Martha Savage on their farm 9 miles north of Almena Kansas. Many early pioneers to Nebraska and Kansas lived in sod houses at first, because timber was scarce. Most people did not want to live in a soddy very long. Sod invariably left dust and dirt on their floors, furniture and clothes. Mothers hated them because the homes were so unsanitary for their children.

Bogey had little schooling, but learned to read and write and figure arithmetic. He took a correspondence course in mechanics, although he had no car, he road a bicycle to town and to farm sales.

He installed a gas pump at Rayville. He sold gas, old parts and iron from items he bought at farm sales. He recorded everything and was enthusiastic about nature with a special interest in butterflies, according to an article by the Norton County Genealogical Society.

Bogey Savage, a bachelor, lived in a sod house most of his life. It seems a little dirt never bothered him. At first view, his sod house looks as if it were hugging the land. Plants and grass grew around it. He piled boards against the walls to keep them from washing away during hard rains. A ladder led up to the roof, where Bogey had piled other boards and sheet metal to keep the rain out.

A stove pipe went outside and up over the roof. His stove was his source of heat and cooking. He slept by the stove in the winter to stay warm. He rarely bathed, but when he did, he used a wash basin. He was a survivalist after seeing the grasshopper disaster in the 1890s and the Great Depression in the 1930s, Bogey had learned to survive on very little. He traded eggs and vegetables for other food, he slaughtered his own beef on the farm and milked cows. He cherished his resources. He wore the same pair of coveralls for years at a time. He had a long white beard, a straw hat, and dark gray eyes.

In search of more information about Bogey Savage, I traveled to Almena, Kansas, in summer of 1996, with Arlen Lazaroff. We interviewed people in the senior citizen center who remembered Bogey. An old timer said, “I remember putting up hay with Bogey.” A lady said she saw him bathe in the public fountain on Saturday nights. Another lady Marjorie recalls singing at his funeral at the Almena Congregational Church in 1950.

Ray Marble, who was 73 years old at the time of our interview, remembered when Lynn Keith went hunting at Bogey’s place and nearly got killed. Bogey, hiding in his tunnels, rose his head like a periscope on a submarine, aimed his gun and shot it above his head. The hunter hightailed it out of there and never went back.

Bogey Savage remembered World War I and World War II. He was spooked about the possibility of foreign planes penetrating the American borders and bombing cities and towns. His paranoia was probably unwarranted, but not uncommon for someone who is a hermit. He felt comfortable sitting below the surface of the Earth in a tunnel with a candle, a jug of water, peanut butter and crackers, and a little dried meat and cheese.

Another strange, or perhaps crude behavior was the way Bogey Savage urinated in public. He would urinate into a cup inside his coveralls. Then he carefully removed the cup from his coveralls and poured the contents on the ground.

Bogey’s sod house was at Rayville, a tiny town established in 1884, which had a post office, general store, a millinery store, blacksmith shop and drug store.

Bogey Savage made and rode his own bicycle. The bicycle is made out of wood and iron.

“If you could look beyond his bizarre behavior, Bogey was an interesting man,” Marble said. “He was a friend, a gentleman and a scholar. Bogey and I got along well. He always talked. He could talk about everything.”

Bogey once predicted Chrysler would make a car that would get 70 miles per gallon. Well he’s almost right on that, there are cars that get 55 to 60 miles per gallon right now.

Bogey, who had been through all kinds of difficult weather, especially during the Dirty 30s, predicted that the Marble brothers “will live to see the day it freezes every month here in Almena. I won’t, but you will.” That prediction has not come true. Every fall Bogey asked Ray Marble’s father to pick up a barrel of peanut butter and a case of crackers when he trucked cattle to Omaha. Bogey lived on that through the winter. In the summer, he ate vegetables and wild game.

Old-timers remember his mother Martha telling her husband, Charles Sr., to fix the roof on the old sod house, but he refused. As he went outside, she told him to keep on going, and don’t come back. And he never did. One time Bogey went inside a grocery store, stood on the heat grate and smelled up the area around him. The employees couldn’t stand it.

In 1945, he caught pneumonia and Dr. Herbert Bennie brought him to Almena to live in an old store building. Bogey Savage, 71, died on Aug. 15, 1950. He was buried in the Almena Cemetery. Survivors included his two sisters, Mrs. Gertrude Hill of Lucas, Kansas; Mrs. Alzora Rodenbaugh of Guthrie Center, Iowa; two brothers William Savage, Fontanelle, Iowa; and Arthur Savage of Fall Brook, Calif.

After his death, a brother sorted through his belongings, saved the things that were valuable to them and bulldozed the house and wood into a pile to be burned. The corner where he lived is now farmland.

Bogey Savage was a highly distinctive pioneer in Kansas. I admire how well he managed his resources, riding a bicycle to Almena and farm sales, and running his farm, living so frugal yet carefree; his love of nature and his fondness for butterflies.

S.P. Dinsmoor

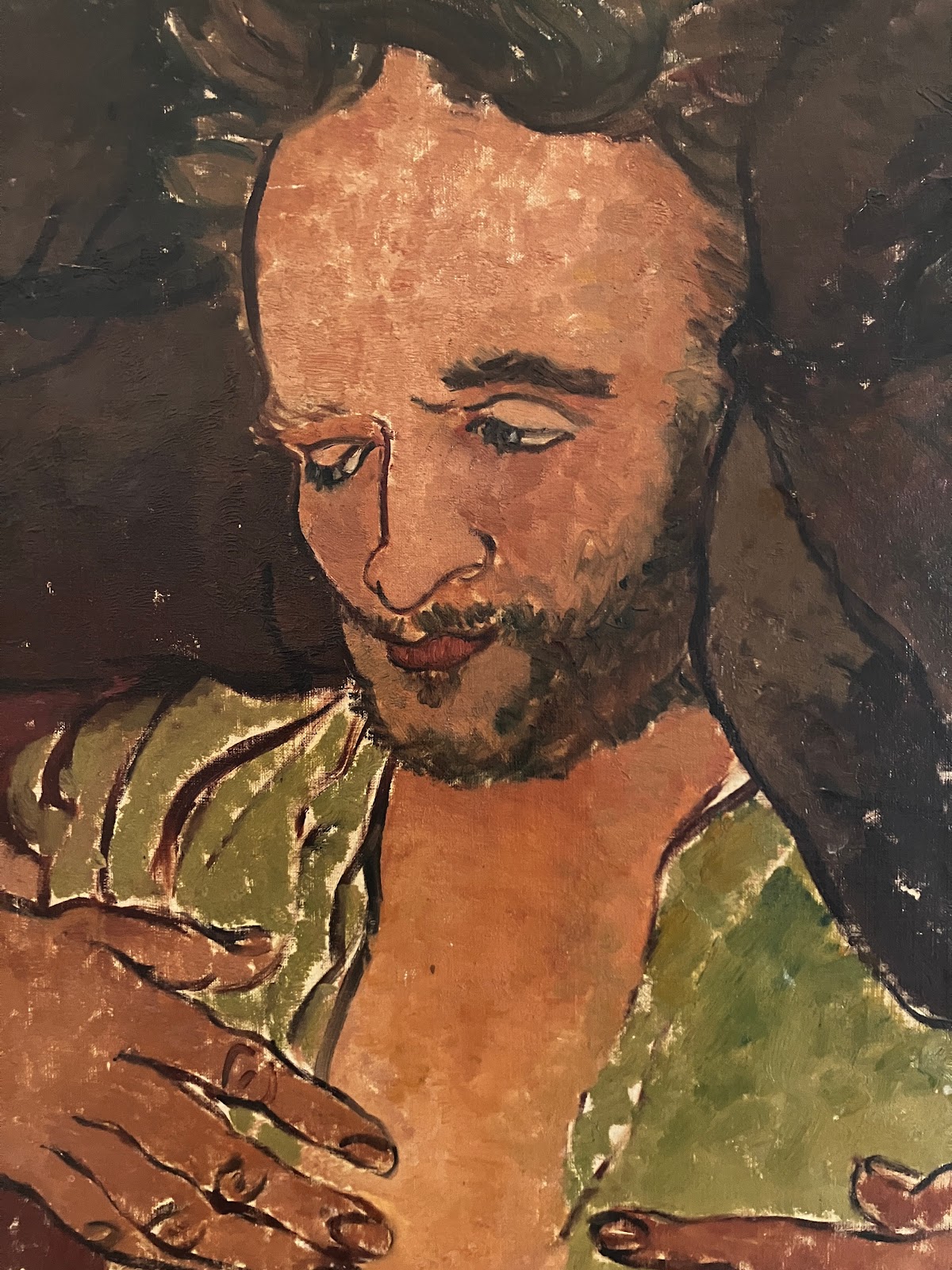

S.P. Dinsmoor is the quintessential eccentric Kansas man who is now iconic for his concrete sculptures in Lucas, Kansas.

His Garden of Eden carries mythic status among folk art connoisseurs. This man’s life is worth exploring for his views on politics, religion, humanity, the plight of the black man, and religion.

He was a thought-provoking man who read everything he could. He would challenge anyone on virtually any topic because he was so well read. He was a school teacher and a farmer, in addition to being an artist. I think he represents everything that is good about Kansas, a man with strong conviction builds over 150 statues in his garden. He dies in 1932 yet he is so beloved there is support for his sculpture garden today. Visitors are encouraged to tour the Garden of Eden in Lucas, Kansas.

I was lucky to interview Dinsmoor’s daughter Emily Jane Dinsmoor Stevens. My friend Joe Mettenbrink introduced me to her in 2004. In Omaha, I met Emily and Emily’s daughter, Janet Stevens Holmquist Smith, and my friend Joe.

Dinsmoor married Frances Barlow Journey in 1870. After she died in 1917, he married Emily Brozek. He was 81 and she was 22 at the time. They had two children. Both died in 2013. She was a true daughter of a Civil War veteran, so I shook the hand of a person who shook the hand of a Civil War veteran.

Daughter Emily was a tiny little girl growing up in Lucas, Kansas. Her father was alive for the first eight years of her life. She remembers him well.

"I always jumped on Daddy's lap whenever I wanted to," she said. "I liked to comb his hair."

Dinsmoor loved to tell stories and often took the opposite point of view in a debate.

"He enjoyed arguing to learn more than he knew," Stevens said.

Adam and Eve, Cain and Abel, the devil, angels and serpents are among the sculptures in his garden.

Stevens said her father read the Bible many times --- twice before he was 16.

"I have managed to read it from cover to cover every year for many years," she said. "I'm still not a scholar of the Bible. Daddy felt he was, and discussed it with any minister who would."

She said the secret to his long life was eating well --- including creamed onions, fish and prunes --- and not getting angry.

"One time, drought was killing two grafted trees that Daddy had over the big tree stump out front," she said. "He rarely got out, but he dragged the hose to it and began watering. He had a stroke and fell down. My mother grabbed him up like a baby, ran up the two sets of steps on the porch, into the den and into the big room where she laid him on the couch. I jumped on top of him, shook him and screamed, 'Oh Daddy, don't die, don't die.' And he didn't. He came to and said, 'How could anyone die with all that racket?' "

Union soldier

He was born March 8, 1843, near Coolville, Ohio. Research by his son, John, shows that Pvt. Dinsmoor was in the 116th Regiment of the Ohio Infantry Volunteers. He was in more than a dozen battles in 1863 and 1864, many in Virginia, including Bunker Hill on July 24, 1864.

He told family that while watching from an orchard tree with binoculars, he saw Gen. Robert Lee surrender to an aide of Gen. Ulysses S. Grant, and not Grant himself.

After the war, Dinsmoor became a teacher. He and his first wife lived in Nebraska for a brief time but lost everything in a house fire, Stevens said.

Dinsmoor began building the Garden of Eden and cabin home in 1907 at age 64. Over 22 years, he used about 113 tons of cement and many tons of limestone and colored sand to create his log cabin and sculptures. The site is now listed on the National Register of Historic Places and welcomes about 10,000 visitors every year. His body is entombed at his home in Lucas, where visitors can see his body if they want.

Garden of Eden Inc., with about 20 members, purchased the site in 1989. They sold the Garden of Eden to the Kohler Foundation in 2012. Kohler Foundation had the resources to do a full restoration of the sculptures, but the foundation does not collect or retain properties after restoration work is completed. The site was gifted to the Friends of the Garden of Eden in 2014, a non-profit formed to care for the site, which retains ownership of the Garden of Eden as well as the adjacent Miller's Park.

Among Dinsmoor's popular sculptures is the "Crucifixion of Labor." Mankind, represented by labor, is crucified while a banker, lawyer, preacher and doctor complacently watch. On one column, an octopus, called "The Trusts," grabs at the world while a soldier and child are trapped in two of its tentacles.

Stevens said the labor sculpture was the last statue Dinsmoor made.

"His sight was failing, and he was not satisfied with the work," she said. "It is unfinished."

Stevens said the labor sculpture reminded her of Jesus.

"I had a friend who said she remembers praying for Jesus to come into her heart and save her," she said. "I said, 'How could I not believe in the one who died for my sins, when I saw him in my back yard every day on the cross.' Labor meant nothing. Jesus did. He was the son of God, and I always knew it.

"I don't remember hearing anything from Daddy to indicate that he believed anything else. People have said he was an atheist, probably because he liked to argue, but you can't make me believe it. He was also very much a Mason."

Stevens said her father introduced her to a Mr. Banks, a black Civil War veteran, who worked for Dinsmoor.

"I knew Daddy fought to free the slaves, but here was a man who fought to free himself," she said.

She said her father was active until he became blind with cataracts.

As he neared death, his youngest children were told he would die.

"You get old, you die," said Stevens. "His last stroke was before his March 8th birthday in 1932, but they still had the big annual birthday dinner for him. He died in July."

Dinsmoor built a 40-foot-tall limestone log mausoleum for himself and his first wife. His body is inside a glass-topped concrete coffin.

Ed Klattenhoff

Long before transgender became a popular issue in America, there was Ed Klattenhoff, who made and wore his own skirts. He also wore women’s jewelry, wig and a hat.

The year was 1988. Shortly after being hired as a reporter job at the Fremont Tribune, I drove to nearby Hooper, Neb., to see if I could find a story or two. Of course I was fond of the name Hooper because that’s my namesake, but the newspaper covered this town as part of our regional reporting efforts. I went to the most popular bar in town and asked the bartender: Who is the strangest, most interesting person in town? The bartender said, “Ed Klattenhoff because he makes and wears his own skirts.”

“Is he harmless?” I asked

“Oh yes," she said. "He is strange but he’s harmless.”

After gathering a few more ideas, I left the bar and went down to Ed’s house and knocked on his door. I told him I was a reporter from the Fremont Tribune, and I was interested in writing a story about him because I had heard he made and wore his own skirts.

He kindly let me into his humble home. His house on Main Street was a small clapboard house with dark carpet and plain walls with picture frames. We sat down in his living room. His octagon shaped table was between his couch and two television sets. It’s built with a block of wood topped with a sheet of plywood stained in oil. Apple cores were scattered on its base. Klattenhoff said he eats an apple a day, it keeps the doctor away. Klattenhoff was 77 years old, and still getting around and living on his own when I met him.

A 1980s Playboy magazine laid on top of his side table next to his chair.

He told me he tried to find a wife. He proposed to a woman many years ago. “We got as far as the doctors office to check our blood and then she went back to her dad’s in Idaho, and that was the last I saw of her,” said Klattenhoff.

So the man adjusted to bachelorhood.

He taught himself how to cook, clean, decorate, and make clothes, while most men would have a wife take care of these duties.

“It’s easy,” he said. “I just follow directions.”

He has baked his own bread for many years. He recently found out he was diabetic so he had to cut back on his baked bread.

Klattenhoff used his hands to make a living as a carpenter, farmhand, plumber, and well digger. His father, Fred Klattenhoff taught him many skills, including well making.

Klattenhoff sews by hand and with an old Singer sewing machine. The machine and cloth are in his living room along with his two television sets, radio, couch, lamp, and gas heater. He admits it’s slightly crowded. Several cotton skirts that he made hang on a table. “I got five of them over there and one on,” he said. The skirts, he said, are comfortable to wear around the house.

Standing there wearing his white cotton skirt and a white T-shirt, he looked like a Chinaman in a laundry.

Although some people might believe that a man wearing a skirt is odd, some neighbors in Hooper don’t seem alarmed by his eccentric ways.

“He’s a fine old gent,” said Marvin Marreel, an auctioneer in Hooper. “He worked hard all of his life. I saw him picking up the mail once in a skirt and I asked him why he wears them and he says, ‘cause they’re cooler than jeans.’”

A woman in Hooper who asked to remain anonymous said women in Hooper consider Klattenhoff odd. “I really don’t think he means any harm to anyone, but you know he wears a wig too,” she said.

Klattenhoff said he wears a pair of coveralls when he goes to town. However, he isn’t afraid to put on a woman’s dress, a wig and jewelry in public. He unabashedly shared his life with me, a reporter.

Klattenhoff came to Hooper in 1946 from Stanton, Nebraska. He served three years in World War II on the islands off the south coast of Alaska. The military maintained a presence on the Aleutian Islands because of threats from Japan.

“People always asked me if there were a lot of women out there,” he said. “Yes, I say, one behind every tree. But there were no trees.”

He was discharged in 1945. He hung the American flag on his wall. When the weather improves, he hangs it on his flagpole in his front yard. Klattenhoff said he is content in his home and happy in Hooper. "It’s a good town," he said, "there is a lot of interesting people here."

A few days after that story was published I received a letter from a person who didn’t like the story about Ed Klattenhoff: “Mr. Hooper, I hear people complaining all the time about the Fremont Tribune wondering why they subscribe because there is never anything in it. After reading your article on Ed Klattenhoff, I agree with them more than ever. Why in heaven’s name would you devote that much space to a kook who goes around town dressing in dresses and women’s jewelry and hats. He was kicked out of a bar and told never to come back looking like that. What was there in your article that was newsworthy? Nothing and I’m ready to cancel.”

My editor, Pat Waters said, don’t worry about that reader, she probably won’t cancel. Waters said Klattenhoff was worth writing about because he’s so colorful.

I ended up writing several stories about Hooper, Neb., including about its Head Start program for children, but none as unique as the Klattenhoff story. He was certainly a man in touch with his feminine side.